CROSS PURPOSES:

The Imagination of Christian Late Antiquity

The Imagination of Christian Late Antiquity

By Leonard George

VOICES IN THE AIR

During the reign of the Emperor Tiberius (14 - 37 A.D.), so it was told, a small ship set sail from Egypt's Nile Delta. Laden with passengers and cargo, the craft was bound for Italy. One evening, the ship drifted past the uninhabited isle of Paxi. The travellers were washing down their supper with wine, savoring the Mediterranean sunset. Some had already nodded off. Thamus, the Egyptian pilot, was perched at the stern, adjusting the long wooden oar that ruddered the craft. It would have been a quiet, peaceful moment - the mainsail flapping in the light breeze, water rippling against the lead-sheathed hull, seabirds swooping for meal scraps bobbing in the wake. The first time it happened, some perhaps blamed the wine for slipping up their senses. But by the third time, everyone had heard it: a voice, wafting over from the thickly wooded shore. A voice too clear and loud to have come from a human mouth at such a distance. Most disturbingly, a voice addressing the ship's pilot: "Thamus! Thamus!"

All eyes swung to stern. The Egyptian, now pale, stared at the shore. When the voice called again more insistently - "THAMUS!" - he stood and listened. "When you get across to Palodes, announce that the Great Pan is dead!"

For long minutes, no sounds but the mainsail, the water and the birds. Huddled in the falling dark, no-one dared speak, for fear of interrupting another broadcast from what could only be a mighty daemon. Finally, a passenger asked, "Well, Thamus! What are you going to do?"

The next morning, after an uneventful but sleepless night, the travellers spied the island of Palodes looming ahead. Thamus had opted to let the weather decide: if there was wind and wave, he would not try to shout against it; but if the sea was smooth, he would make his announcement. As it turned out, the air was calm. The ship sliced across the mirror-like surface, as close to the deserted coast as Thamus dared to take her. The rocks seemed to be watching. Gripping his oar for support, he shouted at the barren landscape: "The Great Pan is dead!" Instantly, the air filled with wailing and shrieks. The silent passengers, lining the rail, shivered in fear. As far as they could see, they were completely alone.

***************

This incident was reported, third-hand, by the pagan writer Plutarch in the late first century A.D. (1) He was trying to explain the sagging belief in the great antique oracles, such as Delphi and Cumae. The tale suggests that the spirits known as daemons are mortal, although they may be incredibly long-lived. If the oracle sites were operated by daemons, not by immortal gods as was commonly held, the passing of these patron spirits could bring about the oracles' demise. Christian communities drew a different lesson from Plutarch's report. Following Hebrew lore, the Christians considered both pagan gods and daemons to be devils. For them, Great Pan's death signalled the dethronement of Satan and his minions, including all the old nature spirits and deities.

While pagans and Christians were split in their understanding of the hidden world, few in either group questioned its existence. The imagination, cast as a dimension of reality, was no trivial feature of the pagan and early Christian world views. This otherworld was thought to be a vital field of action, reflecting and affecting events in the sensory realm. The struggle between pagans and Christians that dominated late antiquity was largely a war for control of the imagination.

TO METAXU: THE INVISIBLE BATTLEGROUND

In the cosmology of the ancients, the things around us are made of four elements - earth, water, air and fire. Far above us spin the great spheres of aether, in which the planets and stars are embedded. In between lies the aerial world. Its stirrings touch us as wind, and we glimpse outlines of its forces in churning clouds and swaying trees. But, in itself, it is invisible. This intermediate realm (Greek to metaxu, "the between") is the haunt of the daemons. Its existence was affirmed by no less an authority than Plato. In the Epinomis, for instance, Plato's character "The Athenian" states that aerial spirits "are wholly transparent; however close they are to us, they go undiscerned" (2). They are telepathic, constantly sampling the stream of human thoughts. Interfacing the above and the below, the denizens of "the between" are literally middlemen, interpreting the terrestrial to the celestial (the gods), and vice versa. Their contacts with human consciousness occur, says the Epinomis, via what we today call the imagination: "appearances in dreams of the night, oracular and prophetic voices heard by the whole or the sick, or communications in the last hours of life" (3).

Paul of Tarsus, the first "Christian" (as opposed to member of a "Jesus movement"), seems to have agreed with Plato, and the pagan vision generally, in recognizing to metaxu. In his letter to the congregation at Ephesus, Paul blames a spirit for seducing "the children of disobedience" (followers of Jesus who disagreed with Paul's interpretations) - a spirit he identifies as "the prince of the power of the air" (4).

Early Christianity found itself in a delicate spot with respect to the kingdom of the air and its imaginal imprints. On the one hand, it was the lair of the demonized daemons of paganism. Imaginings might well be lures of those evildoers, as Paul implied. However, Biblical tradition was clear that God had often called humanity in the past through dreams and visions, sometimes conveyed by an aerial being of a different sort - God's "messenger" (Greek angelos), the angel. The problem was one of sorting the origins, divine or devilish, of imaginative experiences.

Children in Sunday school today are often taught that the history of the church is like a tree. The glorious seed was the life of Christ. His teachings were preserved after his death by the apostles, who carefully passed them on to their successors, the priests of the church. This "apostolic succession" forms the trunk of the tree, and represents orthodox Christian faith. The eleventh century saw a fork in this trunk, with the fission of Eastern and Latin Catholicism; another fork occurred in the sixteenth, with the Protestant Reformation. But all of these mainstream variants preserved the heart of Jesus' message. Since earliest times, however, many branches have grown away from the trunk. These deviations are the heresies - foolish attempts to revise the Truth, sooner or later fated to dead-end in mid air.

Most historians today do not subscribe to the tree model. History, it has been said, is written by the winners. The Sunday school version of Christian history was crafted long ago by the winners of the fight for imaginal dominance that raged through late antiquity, from the first to the end of the fourth centuries. The war was waged not just between Christian and pagan, but equally between groups of Christians. The victors called themselves orthodox, and dubbed the losers heretics.

But long before the end of the war was in sight - say, in 100 A.D. - an observer of Christian groups would not have had an easy time guessing which of the competing "Christianities" would eventually prevail. It was not until 381 A.D. that the Catholic sect became the only officially sanctioned religion of the Roman Empire. In the centuries before this triumph, Christianity resembled not a tree with clearly defined trunk, but a tangled thicket of possibilities, lacking a central dogmatic authority. As historian Lisa Bitel put it, these were the "wild and democratic days" of the church (5).

Viewing this era from the vantage of imaginal history reveals much about how the thicket became a tree. Disagreements over how to bridge the treacherous space between earth and heaven lay near the heart of the controversies between the Catholics and their alternatives.

SHEPHERD FROM HEAVEN: THE EARLY CATHOLIC IMAGINATION

One of our windows into the proto-Catholic imagination is a peculiar text called The Shepherd, written sometime between about 90 and 150 A.D. This work was one of the best-loved Christian reading materials of antiquity. In the late second century Irenaeus, the first great Catholic theologian, quotes it as holy scripture. It was read aloud at services of worship, and is found in some versions of the New Testament as late as the fourth century. Both its fame and its eventual removal from the canon of approved texts are telling indicators of the shifting links between Catholicism and the imaginal world through this period.

The Shepherd's author was Hermas, a former slave in Rome who became a householder and businessman of no great success Hermas and his former owner, a woman named Rhoda, were Catholic Christians. The Shepherd opens as Hermas helps Rhoda step from the Tiber River after her bath one day. Although Hermas insists that he loves Rhoda only "as a sister", he admits that this incident stirs a fantasy: he wonders what it would be like to have a wife like her. An innocuous passing thought - except Hermas already has a wife, and children too. For a Catholic, such fancies veer menacingly close to adultery. Hermas is disturbed by his idea, perhaps suspecting that the "prince of the power of the air" is responsible. (Although, as Dante and Beatrice would show again a millennium later, the erotic tension between chaste souls sometimes craves discharge through visions.)

Mental stress can open a person to strange experiences. It is then unsurprising that Hermas, no doubt in some inner conflict after his encounter with the tempting Rhoda, falls into a "slumber" while strolling in the countryside. This mental state is apparently no ordinary sleep, but a trance. He suddenly finds himself in another world: a Christian province of "the between". He is on a broad plain. Before him appears Rhoda, who scolds him for the "wicked desire in his heart". She vanishes into the sky, leaving Hermas in a panic. Another vision dawns: this time, an old woman in dazzling white, sitting on a fleece-lined chair and reading a book. She reveals to Hermas that his permissiveness with his faithless children and lying wife are the root of his problems. She also discloses that the rule of the Lord is imminent. Then, she is carried off to the east by four angels.

At first, Hermas thinks this woman is the Sibyl, a wisdom character from pagan and Jewish literature. But, he learns in a further revelation, she is none other than the (Catholic) church itself. After his weird encounter, a year goes by. Then, while visiting the spot where his first trance happened, he is again transported to the visionary plain. The old woman appears, once more urges him to correct his errant family, and gives him a powerful message that overwhelms his comprehension. Hermas fasts and prays for the next fifteen days before the revelation becomes clear in his mind. It is a warning: Christians who repent will be forgiven any sins committed up to the day that Hermas publishes his visions; sins done thereafter will be unforgiveable. After this vision, the door of revelation remains ajar for Hermas. Over time, he learns to trigger visions through fasting, praying and chastity. Through these consciousness-altering techniques, Hermas becomes a kind of proto-Catholic shaman.

There is a moral dimension to Hermas' advice. One of his fasting rituals is interrupted by an angel, who mocks him for taming only the outer appetite He must also uproot the evil desires within. The food left uneaten during a fast should be donated to the poor. (Taking instruction from a spirit about the right way to do a ritual is a standard feature of shamanism).

The rest of the text details Hermas' further visions. The Church-woman returns repeatedly, becoming younger as Hermas gradually reforms his life. These imaginings are presided over by an angelic shepherd, from whom the entire work takes its title.

Among the most astonishing passages is Hermas' tale of his out-of-body journey to the lush pastoral setting of "Arcadia". The horizon is a ring of twelve mountain peaks. In a central valley is a huge white rock. Here, at the heart of this mandala-landscape a crew of virgins builds a stone tower. With mounting anxiety Hermas finds himself the center of their attention. They kiss and hug him, lead him in dances around the tower, and finally insist that he lie down with them - of course "as their brother, not their husband". Hermas spends the night there, gets another reminder that Christians are running out of time to repent, and is whisked back to his physical body. The New Testament would certainly have had a different flavor if texts like this had been kept.

So why was it not? The Shepherd is impeccably Catholic. Throughout his work, Hermas remains devoted to the Catholic church, and he sent the book to his bishop for approval. The calls for repentence are certainly not unorthodox. One passage even honors the Catholic martyrs, describing the glorious place reserved for them at the right hand of the Lady Church. Hermas seemed to be doctrinally correct. But the Catholic movement had growing political requirements too.

Hermas' imaginal beings clearly sympathize with the poor, and criticize the selfishness of the burgeoning Catholic elite. Although Hermas sought a bishop's blessing for his work, priests and bishops are nowhere praised in the book itself. Only the "elders" of the church are esteemed by the Lady. These elders were Christian community leaders before the rise of the hierarchy that became the church bureaucracy of later centuries. In this regard, the historian Wayne Meeks wrote of The Shepherd's prominent "countercultural tendencies". Harry Maier, another scholar, noted that Hermas' thrust is toward isolating the church from the outside world, rather than achieving dominance within it. (6)

The agenda of the Catholic movement was, however, going in the opposite direction. Membership in other Christian groups was swelling. If the Catholics became complacent, they might indeed become marginalized and powerless within the Christian domain. Even though The Shepherd generally upheld Catholic primacy through its figure of the Lady, it had elements that could be cited as attacking the legitimacy of a centralized power structure in the Church. That Hermas, who was neither priest nor bishop nor even an elder, could claim divine revelations had subversive possibilities. If spiritual entrepreneurs could make direct visionary contact with the Divine, then why should they consult religious brokers like priests and bishops? By the time Eusebius wrote his church history in the early fourth century, he was able to note that The Shepherd, despite its esteem among bygone church fathers, "cannot be placed among the accepted books" (7).

THE PERILS OF PERPETUA: PURGATORY SPIED

Were visionaries like Hermas rare among early Christians? Hermas was unusual in making such a lengthy and coherent record of imaginal contacts. But there were other "prophets" among Hermas' contemporaries. These wandering holy people were the revered guests of Christian groups, including the Catholics. Their spiritual gifts included dreams and visions, thought to be inspired by God. Indeed, imaginings were highly valued by many ancient Christians.

The martyrs were the heroes of the early Catholic church. No feature of their lives was reproachable. Because martyrs had revelatory dreams and visions, the faithful accepted that at least some imaginings were valid. The precedent was set by Stephen, the first martyr. The Book of Acts (7:55-56) says that Stephen described a vision of God and Christ shortly before he was stoned to death. Another early martyr, Polycarp of Smyrna, testified that he knew his fate even before his arrest. He had dreamed that his head rested on a flaming pillow, and understood that he would be burned alive.

The most poignant and revealing item in the literature of martyr's imaginings is the diary of Perpetua. She lived during the reign of Septimius Severus. In 202 A.D., the Emperor declared conversion to Christianity a crime. At the time, Perpetua was not baptized, but she belonged to a group of "catechumens" - Christians preparing themselves for the baptismal rite. They were placed in a Carthaginian prison to await execution. Perpetua had likely heard stories of other martyrs' comforting visions, so she requested them of God. She did not record her exact method of doing so, but she wrote down the content of a series of visions that came to her, up to the night before her death.

Like those of Hermas, Perpetua's images are surprising and richly symbolic. In her first vision, she sees a ladder rising to heaven, bristling with arms. At its foot is a dragon. Mounting the beast, she rides to a garden. There, a shepherd in white (shades of Hermas) gives her cheese to eat. Perpetua understands this to mean that she will be martyred. In another vision, she visits a different garden where she sees her dead brother in torment, vainly trying to quench his thirst at a fountain. She prays for his release. Historian Jacques Le Goff noted that this vision is the first recorded sighting of purgatory in Christian history (8). (Vision reports played an important role in the campaign to put purgatory on the official reality map in the Middle Ages.) Strengthened by her visions, Perpetua died impressively. Unflinching, she allowed herself to be mauled by wild animals in the arena. A young gladiator was sent out to finish her off, but he was overcome by emotion. She reached out and guided his hand to her throat.

SAVED BY A DREAM

Tertullian, the first Latin church father, observed that the martyrs' spilled blood acted as the seed of faith. Some pagan witnesses to martyrdom were so moved that they became Christians, and even martyrs. Thus did Tertullian himself find Christ. By helping martyrs bear their fate with dignity, dreams and visions assisted in laying the foundation of the Catholic church. In many cases, an imaginal encounter led directly to conversion.

Tertullian made the following observation, amazing in light of the low profile that the imagination has in modern Christianity: "Most men owe their knowledge of God to visions " (9). Another church father, Origen, noted that even anti-Christians had entered the fold in this way: "Many came to Christianity in spite of themselves, a certain spirit having turned their hearts from hatred of the doctrine to resolution to die for it by presenting them with a vision or dream. I have seen many examples of this." (10)

Tertullian was the first major Christian theorist of the imagination. He devotes five chapters of his work De Anima to an analysis of dreams and dreamlike states. Tertullian was a scholar well-versed in pagan opinions, and adapted the wisdom of the ancient world to Christian concerns. Everyone dreams sometimes, claimed Tertullian. The season, diet, bodily position, and time of night, all affect the likelihood of dreaming. Meaningful dreams are not limited to special settings, such as the incubation temples, Tertullian taught. During a dream the soul leaves the body - "it wanders, flying here and there, and remains free." (11)

Tertullian held to the general Greek and Hebrew suspiciousness about the imagination. He thought that many dreams are the productions of lower spirits - "No one can doubt that houses are open to demons and that men are encircled by images." (12) The wandering soul could easily meet one of these images, but should not trust it. Apparitions of the dead, either waking or dreaming, are certainly demonic illusions, as the deceased are either in heaven or hell, or awaiting resurrection at time's end. But God could also send images to the soul - "Who could be so alien to the human condition that he never once perceived a faithful vision?" (13) Prophetic and premonitory dreams may come from God, but can also be faked by devils. Tertullian also endorsed the visions of trance states, and, like Hermas, recommended fasting to provoke them.

IN THE MIND OF A CHRISTIAN WIZARD

Along with dreams and visions, many ancient Christians were fascinated by the use of magic rituals to stir the imagination. Such practices can hardly be classed as either "orthodox" or "heretical". They might be called "sub-orthodox": unbothered by the fine points of dogma, and convinced of the power of religious symbols, magicians simply aimed to use that power. To hedge their bets, practitioners mixed elements from several traditions - pagan, Hebrew, Christian - regardless of the clash of doctrines.

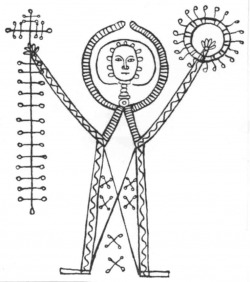

Several spellbooks, known as "wizards' hoards", have survived from Christian antiquity. These collections were written on papyrus, parchment or vellum and sometimes buried in jars for safekeeping. Most of them have been found in Egypt, preserved by the dry climate. Chanting phrases and sounds, beseeching supernatural forces to aid the cause, and visualizing imaginal beings are stock features of the spells. To inform the mind's eye, pictures of the spirit or deity illustrate the spell-texts.

A fine example of old Christian magic may be found on a parchment sheet now housed in the British Museum (14). The spell was commissioned for "Sura daughter of Pelca", to guard her during her pregnancy. The magician invoked "Yao Sabaoth"(a name of God), Jesus, the commander of the seven archangels, and a host of other angels and heroes. The magician would have contemplated the image of Yao Sabaoth, fixing it vividly in his mind. Then, he would have called upon the deity to descend and animate the picture: "I adjure you by your name and your power and your figure and your amulet of salvation and the places where you dwell and your light-wand in your right hand and your light-shield in your left hand and your great powers standing before you." The text is rife with bizarre words of power - "OHI SHAOHI SHASHAOHI SHAOHI SHA AAAO". They were probably chanted many times to intensify the vision; to this day, Tibetan tantric practitioners recite similar mantras during their sadhanas, or visualization ceremonies. Sura's request would then have been presented: "Cast forth from her every doom and every devil ... and every evil eye and every eye-shutter and~ every chill and every fever and every trembling. Restrain them all. ... Do not permit them ever to visit her or the child with whom she is pregnant for approximately two hundred miles around." Some lines of the text are marked with rows of crosses, reminding the magician to seal his words with the sacred gesture.

IMAGINAL SALVATION: THE GNOSTIC ALTERNATIVE

Dreams, visions, imaginal magic - the border between the early Christian world and to metaxu was a busy one. Catholic fears about this fantasy traffic were heightened by the imaginative dealings of "the children of disobedience". Many of the Christian schools that disagreed with Catholicism on doctrinal matters also had strong interests in the imagination. Foremost among these were the Gnostics. Gnosticism was not a unified body of thought; indeed, not all variants were even Christian. What the Gnostics held in common was the notion that salvation is possible only through gaining a special type of knowlege (Greek gnosis, hence their name).

What is gnosis? It is not knowledge about the sensory world, or logic, or ideas, but insight into the heart of one's own being. The Gnostics claimed that real self-knowledge is the same as God- knowledge. One's deepest identity is divine. This realization is necessary and sufficient for salvation, an awakening similar to the Buddhist enlightenment. Some historians have wondered about direct links between Buddhism and Gnosticism. Buddhists from India are thought to have visited the Egyptian city of Alexandria, which became a hotbed of Gnosticism, in the first centuries A.D. But we have no records of their activities. Buddhist influences on Gnosticism remain an intriguing speculation.

How can the liberating insight of gnosis be attained? Historian Elaine Pagels found that Gnostic Christians sought Truth through four avenues: the apostles' teachings familiar to all Christian groups; a body of wisdom allegedly taught by Jesus to the apostles in secret, and transmitted through esoteric lineages; the instructions of famous Gnostic visionaries like Basilides and Valentinus; and first-hand imaginal contacts with the Divine (15). The Catholics accepted only the first of these, and asserted monopoly rights over it.

The contents of the New Testament are like a spoonful taken from the sea of Christian literature that existed in ancient times. Many, maybe most, of these texts were Gnostic. A number of these were "gospels", "acts" and "letters", such as we see in the New Testament. Others were myths of the creation of the world and humanity's source, lessons of wisdom figures, and metaphysical tracts. Through lucky accidents of history (see below), a few of these heretical works managed to survive to the present. And they are rife with references to imagination.

For instance, a passage in the Gnostic Gospel of Truth describes how ordinary awareness, conditioned by lack of gnosis, is a false imagining akin to a nightmare:

"They were ignorant of the Father, he being the one whom they did not see. ... as if they were sunk in sleep and found themselves in disturbing dreams. Either there is a place to which they are fleeing, or without strength they come from having chased after others, or they are involved in striking blows, or they are receiving blows themselves, or they have fallen from high places, or they take off into the air though they do not even have wings ... [other nightmare scenarios follow] ... When those who are going through all these things wake up, they see nothing, they who were in the midst of all these disturbances, for they are nothing. Such is the way of those who have cast ignorance aside from them like sleep ... The knowledge of the Father they value as the dawn." (16)

Everyday life is based on a wrongly imagined notion of the self. The result is a nightmare of unnecessary, futile, anxious activity. Gnosis ("knowledge of the Father") is a wake up call. In the dawn light of truth, we see that our terrors are made of "nothing". The awakening can come in the form of a vision - a true imagining.

VISITS AND JOURNEYS IN THE GNOSTIC IMAGINATION

Two kinds of imaginal experience are outlined in Gnostic texts - visitations from divine realms, and otherworld journeys. Sometimes, these happen within the same story. The Acts of John contains a well-known example of the imaginal visit. The apostle John cannot bear to watch Jesus being crucified, so he hides in a cave in the Mount of Olives. Christ comes to him as a glowing apparition, and projects the image of a "Cross of Light". The Cross is surrounded by a scattered crowd. Within the outline of the Cross is another crowd, which is united into "one form". These are the Gnostics, gathered for salvation. Just as the appearance of the Lady Church changed to match Hermas' growing purity, so also in the Gnostic stories. Christ was seen and heard variously, depending on the visionary's spiritual maturity.

The other type of imagining found in Gnostic texts is the journey to a divine realm. These accounts resemble the Jewish otherworld journey literature, such as the Book of Enoch, and feature the same kind of layer-cake heaven. For example, The Apocryphon of James tells what happened to the apostles James and Peter after the risen Christ left them in "a chariot of spirit". They knelt and prayed, and

"sent our hearts upwards to heaven. We heard with our ears, and saw with our eyes, the noise of wars and a trumpet blare and a great turmoil. And when we had passed beyond that place, we sent our minds farther upwards and saw with our eyes and heard with our ears hymns and angelic benedictions ... After this again, we wished to send our spirit upward to the Majesty ..." (17)

It is unlikely that the visions recorded in Acts of John and The Apocryphon of James are true accounts of John's and James' experiences. But these tales were not read for mere entertainment or uplift. Rather, they described the kinds of imaginings that the Gnostic could expect to have as signs of spritual progress - in historian Dan Merkur's words, "as exemplars of the living practice of visionary experience". (18) The confidence so created would spur the visionaries in their own practice.

Catholic critics also attested visions among the Gnostics. Hippolytus, in an anti-Gnostic polemic, reported that "Valentinus says he saw a small child recently born and asked him who he was. The child replied that he was the Word." (19) This Christ-ghost then gave Valentinus the wisdom of salvation. According to Irenaeus, the Gnostic Marcus learned his own true origin and identity from a female being that came down from a realm of light (20).

VISION-QUESTING, GNOSTIC STYLE

Clearly, the Gnostics treasured their visions. But how could an imaginal experience, whether visitation or journey, unveil the redeeming gnosis? In the case of visitations, Gnostics might recognize that the divine beings they were seeing were actually images of their own true selves. As The Gospel of Philip put it, "what you see you shall become." (21) If Christ appears in visions, as he reportedly did to Valentinus, then the visionaries can "become" Christ - or, more precisely, they can wake up to the fact that they already are. The otherworld journey also equated Gnostics with Christ, in a less direct way. Jesus was resurrected from the dead; and the Gnostic visionary's rise through the heavens is also a resurrection, a reversal of the spirit's original plummet from the light-world into the nightmare of ordinary consciousness. The Gospel of Philip: "It is certainly necessary to be born again through the image. Which one? Resurrection. The image must rise again through the image." (22) Whether through recognizing a Christ-image as a self-image, or by undergoing an imaginal resurrection, visions could lead the Gnostic toward gnosis - self- knowledge as God-knowledge.

Such valuable experiences were not just passively yearned for. They were surely sought. Unfortunately, none of the Gnostic works we have today give clear instructions on how to have visions. But there are some hints. Pagels observed that the text Zostrianos "tells how one spiritual master attained enlightenment, implicitly setting out a program for others to follow." (23) Reining in bodily desires and habits of thought are part of Zostrianos' training. The master finally has his transforming vision, probably while meditating: "It came upon me alone as I was setting myself straight, and I saw the perfect child". (24) (Later, he travels in a "light-cloud" through the terraces of the otherworld.)

The Dialogue of the Savior tells a story in which praying and "laying on of hands" opens the vision-door (25). The Letter of Peter to Philip recounts how the apostles prayed, saying "give us power"; Christ then appeared as "a great light" that spoke to them (26). A few Gnostic works contain unintelligible passages, like those in the "wizards' hoards", pointing toward mantric chanting practices. And some museums today possess so-called "Gnostic gems" in their collections. These stones are carved with words of power and pictures of imaginal beings, such as the famed spirit Abraxas (whose name was later garbled into the magical utterance ABRACADABRA), shown with a rooster's head and snakes for legs. They might have served as meditation objects, or simply as amulets to keep harm away from entranced visionaries.

CHRISTIAN TRUTH: EMBALMED OR FRESH?

The Catholic tradition insisted that everything a Christian needed to know for salvation had been given to the apostles by Christ during His earthly life, and for a brief time after the Resurrection. The knowledge of this "faith once delivered to the saints" (27) was guarded by the apostles' successors - the bishops and priests. Truth, being changeless, was not open to revision. Any later revelation claims had to be judged quite skeptically, against the yardstick of ecclesiastic teachings. Gnostic spiritual freelancing went against this grain. Christ, the Gnostics said, was still granting new truths directly to humankind, through the imagination. Furthermore, the Christ-status of Jesus was not unique - the enlightened Gnostic "is no longer a Christian, but a Christ". (28) The Gnostics' sense of truth was not static, "once delivered", but dynamic. Truth, like food, is only good when freshly prepared and digested until it becomes the very substance of the self; old tales of others' feasts nourish neither body nor soul.

The fathers of the Catholic church saw clearly that Gnostic ideas undermined their authority. If I can consult Christ directly in a vision - if I am a Christ myself - why should I defer to the opinions of a priest, who relies on doctrines written down long ago? Irenaeus, arch-enemy of the Gnostics, mocked their continuous production of fresh revelations: "every one of them generates something new every day, according to his ability; for no one is considered perfect who does not develop among them some enormous fictions." (29) And Tertullian caustically noted the outcome of this spiritual anarchy:

"(Gnostics) enter on equal terms, they listen on equal terms, they pray on equal terms ... they do not care if they profess different doctrines, provided that they all help to destroy the truth. All are proud, all promise knowledge. ... And heretical women, how brazen they are! They dare to teach, to dispute, to exorcize, to promise cures, even perhaps to baptize. ... And so, today one man is a bishop, tomorrow another. Today one is a deacon who tomorrow will be a lector. The presbyter of today is the layman of tomorrow. Even members of the laity are charged with the duties of a priest." (30)

This is no way to build a lasting church hierarchy. The Gnostics were marked, then, as an obstacle to the creation of an institutionalized Christian religion.

AN ANCIENT "NEW AGE": THE MONTANIST ALTERNATIVE

The land once known as Phrygia is hilly, mostly rural country in what is now central Turkey. By the second century it had been a cultural backwater since the legendary days of King Midas. The Phrygians were famed for their disciplined, austere character, which sometimes ran to extremes. Phrygia was the homeland of the cult of the goddess Cybele. Her devotees, the Korybantes, were fond of dancing with drum and flute to the point of trance, in the manner of the classical Greek "telestic mania". The truly enthusiastic, in imaginal union with their Queen, had been known to castrate themselves. The Phrygians' moralistic, dissociative mind-set proved fertile ground for the teachings of Montanus, who set into motion the other main challenge to Catholic dominance within second century Christianity.

Sometime in the latter half of the century, reports reached the outside world about an odd new religious movement - a movement that claimed to be Christian. A recent Phrygian convert to Christianity named Montanus had begun preaching in the region, along with a band of followers. They said that certain gifted souls, including Montanus himself and his two female assistants, Prisca and Maximilla, became mouthpieces for the Holy Spirit while entranced. Unusually for Christian prophets, the divine messages of the Montanists were often expressed in the first person: Montanus said, "I the Lord, the Almighty God, remain among men."(31) Critics derided them for claiming to be God, but the flavor of Montanist prophecy seems more like the "channeling" of the twentieth century "New Age" movement than literal deification. Montanus (or the Holy Spirit through him) compared the prophet to a lyre, and the Spirit to a pick flying across its strings. The parallel to our New Age is underlined by the Montanists' own name for their movement: "New Prophecy".

The message of the Montanists was severe. Remarriage after divorce was strictly forbidden; frequent fasting was required; martyrdom was yearned for; and any avoidance of such a fate led straight to hell. In aid, the Spirit encouraged through mental images. Prophetess Prisca announced, "For if the heart gives purification, they will also see visions. And if they lower their faces, then they will perceive saving voices, as clear as they had been obscure." (32) A later Catholic source stated that one prominent Montanist claimed imaginal flights to the heavens. Montanism, then, was another form of redemptive Christian imagining. It did not offer "becoming a Christ", as did some Gnostic groups; but it did feature an intimacy with the Holy Spirit, and the salvific assurances of visions and voices, in return for a life of fierce ethical rigor.

In the first decades of the movement, Montanist prophets announced that they lived in the "Last Days". With the Lord on the horizon, only fools would bother with an institutional church. Montanus was the first to make the error that has brought down many a millennarian since - he specified the time and place of Christ's return. The little Phrygian village of Pepuza (so little, in fact, that modern researchers cannot find it) was renamed "Jerusalem", and Montanists gathered there at the appointed time. Afterward, according to a Catholic rumor, Montanus and Maximilla hanged themselves "just like the traitor Judas" (33); but this may well be a slur.

Whether or not Christ's non-appearance was fatal to its founder, it was not so for the Montanist movement. Montanism spread throughout the ancient Mediterranean as far as Carthage, and sunk strong roots in the Empire's north African provinces.

Catholics were especially vexed by the movement's support for the spiritual authority of women. Many of the Holy Spirit's chosen vessels were female. Montanist ceremonies would begin with the entry of seven white-gowned virgins, carrying torches. A New Prophetess even reported a vision of Christ as "a woman in shining garments." (34) But Tertullian, incensed as he was by the preaching and exorcising Gnostic women, had no objection to prophesying women (legitimate prophetesses were recognized by St. Paul - 1 Corinthians 11:5), perhaps because they were merely serving as "instruments". In fact, this Father of the church eventually turned his back on Catholicism, and died a Montanist.

ONWARD, IMAGINAL SOLDIERS

By the third century, then, the Catholic sect was imperilled on two fronts. In the material world, there were waves of savage persecution, sometimes state-sponsored; and a smorgasbord of dissident Christian communities to tempt away their flocks. On the front of to metaxu, magicians and visionaries in the Catholic fold threatened to derail the evolution of a centralized spiritual command system. And the subversive potentials implicit in the Catholic prophets were dramatically unpacked by Gnostics and Montanists. The pagans were still very much on the imaginal field too. The seductive claims of the late pagan vision (the Mysteries, Thaumaturgy, Hermetism and Theurgy) proved a lively threat. All of these dangers, within and without, were summarized in the glyph of the Devil. Action on both fronts was needed to save the "faith once delivered to the saints" from his hooves.

Over the course of the century, the Catholic elite devised strategies to gain control of the imaginal gates. One of the captains of this effort was Hippolytus. Sworn enemy of all heresy, he was so offended by the laxity of Pope Callistus I that he set himself up as a counter-Pope in 217, and kept this role throughout the mandates of Callistus' successors Urban and Pontian - the first instance, but by no means the last, when the papacy fragmented. As part of an anti-Christian campaign, Hippolytus and Pontian were exiled to Corsica, where they died.

In the war for the imagination, Hippolytus' contributions were twofold. First, he asserted that the apostolic lineage was not just a transmission of teachings, but of a holy power that granted its holders spiritual authority over everyone else. This power was passed from bishop to bishop. Therefore, only bishops could consecrate other bishops. This notion bolstered the concentration of authority within this priestly class. Not just the interpretation of scripture, but of visions and dreams, was thus the sacred prerogative of high church officials.

Hippolytus also invented a view of history that bracketed its most dangerous imaginal aspects safely far in the past and the future. Against the expectations of Christ's imminent return, which so often fuelled visionary causes like Montanism, Hippolytus offered convoluted Biblical proof that the Lord was not due for another three centuries or so. There was thus a great need for an institutional church, girded with chains of command, to keep the faith until that time. Imagination-based claims to the contrary were obvious demonic ruses.

And what of the ample Biblical precedents for inspired imaginings? What of God's promise in the Old Testament Book of Joel, so beloved of prophetically-inclined Christians: "I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, your young men will see visions."? (35) Ah, taught Hippolytus, that was then. The apostolic age was long past - the Revelation of St. John about two hundred years prior was the last direct gift of the Holy Spirit. Now God's call was not to spiritual exploration, but to a stable church community based on unquestioning faith in its leaders, the divinely charged bishops.

A dominant figure in the next Christian generation was Cyprian, who became bishop of Carthage in 248. Like Hippolytus, he had ferocious disagreements with the papacy; also like Hippolytus, he was caught up in a wave of government persecution. He was martyred in 258. Cyprian's papal conflicts, ironically, were over how best to promote the unity of the church. He felt that church leaders were too soft on schismatics and heretics. Cyprian urged the Catholic church to organize along virtually military lines, like the Roman army itself: lines of obedience radiating from the bishops, weaving together an unbeatable troop of faith, "this holy mystery of oneness, this unbreakable bond of close-knit harmony ... portrayed in the Gospel by our Lord Jesus Christ's coat, which was not divided or cut at all." (36) This hierarchy would be mirrored in the imaginal domain. While all Catholics can have dreams and visions sent by God, those of the bishops (including himself) are the most worthy, wrote Cyprian.

VISION OF PAUL: THE ROOTS OP CHRISTIAN TERROR

The evolving tight-bound structure of the Catholic sect helped it to resist the acids of persecution, temptation and internal dispute better than the more anarchistic Gnostics and Montanists. By the third century's end, the Catholics were the strongest and most numerous Christian movement. Sometime during the century, they had invented another weapon in the war for the imagination, woven of imagination itself.

St. Paul, it will be recalled, mentions an out-of-body experience in one of his letters (2 Corinthians 12). Paul states that his otherworldly trip was indescribable, and leaves it at that. Nonetheless, two centuries later, a detailed description of Paul's soul travels was known in Catholic circles. This faked account - called in Latin the Visio Sancti Pauli (Vision of Paul) - became one of the most important vision texts in Christian history. (37) Its contents set the expectations for later generations of pious astral travellers. Also, "Paul's" lurid vignettes of heretics in hell enriched the imagery of Catholic sermons, scared listeners and readers into line, and launched the "fire and brimstone" tradition of Christian terror- preaching that excites some evangelicals to this day.

In light of Paul's comments in his Letter, the authenticity of the Vision was an obvious problem. It was addressed by reports of a discovery in Paul's home town of Tarsus. Guided by an angel, a Christian citizen had unearthed an old marble box beneath a house rumored to have been that of Paul. The box contained a pair of sandals, along with the text of the Vision. Church spokesmen confirmed that the contents must have been placed there by Paul himself, a time capsule for Christians of the future who, unlike his first century contemporaries, were spiritually ready to handle his hair-raising account of the otherworld.

In the Vision, Paul is first lifted by an angel to a heavenly Jerusalem, the City of Christ: an immense structure of twelve concentric walls and twelve thousand towers, ringed by four rivers of honey, milk, wine and oil. Mounted on the walls are golden thrones, upon which rest the bejewelled spirits of the blessed. More memorable, though, are the following passages, which detail Paul's next stop, a dark land beyond the ocean. Here he finds souls standing in a river of fire, the depth of immersion fixed according to their depravity during life. People "who when they have come out of church occupy themselves in discussing in strange discourses" (38) are in it up to the knees, for example. The moral: avoid those weird heretical books. "Those who did not hope in the Lord" end up in a bottomless pit. An angel rips a cleric's intestines with an iron pitchfork, because he had not led a pure enough life. Another angel mutilates the lips and tongue of a hypocrite with a flaming razor. Magicians are packed together in a pit, drowning in blood. Resurrection-deniers have to deal eternally with a double-headed horror almost two feet long - "the worm that never rests". Homosexuals languish in a cavern of tar and brimstone, or run in a fiery river. And so it goes. In a paraphrase of Virgil, Paul is informed that "there are 144,000 pains in hell, and if there were 100 men speaking from the beginning of the world, each one of whom had 104 tongues, they could not number the pains of hell". (39)

CONSTANTINE'S VISIONARY VICTORY

By the opening of the fourth century, it was by no means sure that the Catholic church had safely weathered the storms of its birth. True, the popularity of Montanism and Gnosticism had ebbed, and the power structure urged by Hippolytus and Cyprian had held together against spates of pagan assaults. The Catholic church had spread and rooted throughout the Empire. But a large group of ultra-strict Christians, the Donatists, had broken away from papal deference and set up their own ecclesiastical system, complete with bishops and cathedrals. Another problem was the growing interest in the Arian heresy. The Arians had demoted Christ from his God- status to that of a kind of super-angel. Furthermore, the papacy itself was riven with squabbling. Gridlocked in debate over the proper etiquette of persecuted Christians, the church electors had failed to agree on a successor for four years after Pope Marcellinus died. An outside observer might have guessed that the Christian experiment was drawing to an end. But then, everything was changed - by a vision, and a dream.

At this time, the Roman Empire was ruled by a "tetrarchy" of four emperors. The eastern and western halves of the Empire were each governed by a senior emperor (the Augustus) and a junior (the Caesar), who was expected to graduate to the senior role upon the passing of the Augustus. In the violent life of imperial politics, however, it rarely happened that way. Constantine became the Caesar of the West in 306. By 311, he was warring with his Augustus, Maxentius, and soon allied with Licinius to topple Maximin, Augustus of the East.

In 312, Constantine and his army were heading toward Rome, where Maxentius waited. The odds were not in Constantine's favor. Five years earlier, another army had been broken trying to penetrate Rome's great walls. Like all of his imperial forebears, Constantine was a pagan. He was likely seeking omens and making sacrifices to Apollo, his favorite god, as confrontation loomed. The strange events that happened next have been reconstructed from the writings of two contemporaries, Eusebius and Lactantius, both of whom heard the story from Constantine's own lips. The accounts vary on a few points, perhaps due to memory errors on the part of our informants, or by Constantine himself. The main features of the visionary events can still be drawn with some confidence. (40)

At noon, Constantine stated, he saw a "sign of the cross" in the sky. Visible on the cross were the words In hoc signo vinces - "Conquer in this sign". That night, Christ came to him in a dream, again bearing the holy symbol, and told him to use it in the coming battle. The next day, Constantine commanded that the shields of his troops be marked with a sign - either the cross itself, or the Greek letters chi-rho. He might also have made a standard to carry into battle, showing a cross mounted by the chi- rho. These letters could have had a double meaning: most obviously, they are the first letters of the title Chrestos (Christ); also, they begin the word chreston, meaning "good" or "useful".

After these preparations - and doubtless, with an army puzzled at his curious orders - Constantine approached Rome, in the vicinity of the Milvian Bridge. Unaccountably, Maxentius sent his troops outside the protective confines of the city to engage the invaders, and was routed. In full armor, the defeated Maxentius rode his horse into the Tiber and drowned. For Constantine, this stunning victory must have confirmed the divine origin of his vision and dream. Suddenly and unexpectedly, Christianity had its most powerful ally ever.

CHRIST EXALTED, CYBELE HUMBLED: THE DEMISE OF PAGAN VISION

The next year, Constantine and Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, which was supposed to guarantee religious tolerance throughout the Empire. The long persecution of the Catholic church was over. Indeed, the jack-boot was now on the other foot. Constantine favored Christians with legal privileges such as exemption from compulsory civic duties, and awarded them powerful government roles. He also transferred money from pagan temples to Christian churches, and sponsored gangs to damage images of pagan deities. Influenced by his chief religious advisor, the Catholic Bishop Orosius, he threw his authority against the Donatists and Arians.

In addition to his newfound piety, Constantine might have been pragmatically inspired to promote the Catholics. The Roman Empire was close to shattering. The old religions, long a binding agent of the diverse peoples under Roman rule, seemed to have lost their unifying effect. The Catholic community, on the other hand, had worked with some success at putting down dissent and entrenching an authoritative elite - an image of an Empire in harmony. It appeared almost tailor-made to serve as a counter to the centrifugal forces tearing at the Emperor's world.

Constantine's government did not officially support direct violence against non-Christians. It happened anyway, from time to time. Under his rule Christian mobs trashed six major pagan temples, sometimes torturing and killing their priests. Christian mob violence grew through the century. After Constantine's death in 337, it was increasingly sanctioned by the state. Aside from an interlude in 361-363, when the pagan Julian ruled the Empire, all of the emperors after Constantine were Christians.

While life for non-Christians, especially visionaries and ecstatics, became less comfortable, the Christian imagination continued to deliver revelations to important figures. One night in 361, the Emperor Constantius I was drifting off to sleep, entering that vision-rich twilight known as the hypnagogic state. He saw by his bed an apparition of his father, Constantine, who warned him of his imminent death. Constantius thus had a chance to resolve his affairs - and he did die shortly afterward.

During this era, imperial favor shifted between the Catholics, the Arians, and various compromise groups. When a faction attained power, they used it against their spiritual competitors. In 367, bishop Athanasius of Alexandria decreed the destruction of all non-Catholic texts in Egypt. Around that time, someone buried a collection of leather-bound papyrus volumes in a jar near the monastery of Pachomius in Upper Egypt. The jar held a mini- library of forbidden texts, most of which were Gnostic classics - the Gospels of Mary, Thomas and Phi1ip, The Dialogue of the Savior, The Apocryphon of James, Zostrianos, and forty-six others. Did someone "cleanse" the adjacent monastery's library, hiding these works from the zeal of Catholic book-burners? Did they plan to retrieve the collection after the trouble blew over? Whoever buried the vessel never returned, their fate unknown. Its existence was forgotten for about 1,600 years. In the interim, almost all trace of the Gnostics was erased from history. In 1945, an Arab peasant mining soil for fertilizer struck the jar. His mother used much of his find as kindling before anyone realized its value. Now known as the Nag Hammadi Library after a nearby town, the surviving texts have given the modern world most of its knowledge of the long-lost Gnostic visionaries.

Triumph ultimately went to the Catholics, but not without one more intervention from "the between". Emperor Theodosius I presided over the final political defeat of the Arians, and proclaimed Catholicism the Empire's state religion in 381. But thirteen years later, the pagan leader Eugenius had Theodosius' co emperor Valentinian II killed, and raised an army to wrest the Empire from the Christians' grasp. The first day of battle between pagan and Christian forces went Eugenius' way. By dusk, Theodosius and his troops were camped on a mountaintop, dreading the morning. That night, the Emperor dreamed. Two men, dressed in white, riding white horses, told Theodosius that they were John the Baptist and the apostle Philip. They would lead the Christians to victory. At dawn, Theodosius shared the dream with his army in a rousing speech: "Hence fear no more! Follow those who are protecting us and fighting at our head." (41) The rest is history, the course of which had once again been touched by the imagination. Theodosius, with his fellow visionary Constantine, are remembered today as the founders of the Christian Empire. Who knows? If these Emperors had not dreamed their dreams, would the American dollar bill today read "In Jove We Trust"?

Plutarch proved prescient. At the dawn of the fifth century, Great Pan seemed dead or dying, along with the visionary exuberance of the pagan, Gnostic and Montanist alternatives. The bishops were digging in as the gatekeepers of the imaginal bridge to God. The rising spirit of the age had truly been captured by Constantine. In the city he named after himself, Constantinople, he erected a statue of a goddess in the posture of Christian prayer. It was Cybele, primal deity of vision and blood, bowing to her new Lord. For the next millennium, the imagination and passion of the West would largely be in the service of the Catholic church.

NOTES

1) On the cessation of oracles, 418E - 419E

2) Epinomis 984c

3) Epinomis 985c

4) Ephesians 2:2

5) Bitel, L.M. (1991). In visu noctis: Dreams in European hagiography and histories, 450-900. Historv of Religions, 31, p.47

6) Maier, HO. (1991). The social setting of the ministry as reflected in the writings of Hermas, Clement and Ignatius. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo Press. Meeks, W.A. (1993). The origins of Christian morality: The first two centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

7) The history of the church 3:3

8) Le Goff, J. (1988). The medieval imagination. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, p.205

9) De anima 47:2

10) Contra Celsum 1:46

11) De anima 46:13

12) De anima 46:13

13) De anima 46:3

14) London Oriental Manuscript 5525. In Meyer, M., & Smith, R. (Eds.) (1994). Ancient Christian magic: Coptic texts of ritual power. San Francisco: HarperCollins, pp. 120-124

15) Pagels, E.H. (1978). Visions, appearances, and apostolic authority: Gnostic and orthodox traditions. In Aland, B. (Ed.). Gnosis: Festschrift fur Hans Jonas. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp.415-430

16) Gospel of truth 28-30

17) The apocryphon of James 15

18) Merkur, D. (1993). Gnosis: An esoteric tradition of mystical visions and unions. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, p.133.

19) Refutatio VI.42.2

20) Adversus haereses 1.14.1

21) Gospe1 of Philip 61

22) Gospel of Phi1ip 67

23) Pagels, E.H. (1979). The Gnostic gospels. New York: Random House, p.135

24) Zostrianos 2

25) The dialogue of the Savior 135

26) The letter of Peter to Phi1ip 134

27) Jude 3

28) Gospe1 of Philip 67

29) Adversus haereses 1.18.1

30) De praescriptione haereticorum 41.2-6

31) quoted in Aune, D.E. (1983). Prophecy in early Christianity and the ancient Mediterranean world. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, p.314.

32) quoted in Aune, p. 315

33) Eusebius, The history of the church 5.16

34) quoted in Aune, p. 315. Robin Lane Fox [(1986). Pagans and Christians. San Francisco: HarperCollins] rejects the authenticity of this report as orthodox propaganda: "it was good male fun to allege that Christ had appeared to the women as a female." (p.405) Given the plethora of female divine beings in contemporary Gnosticism, and occasional references to a female Christ within Catholic tradition itself through history - cf. Hildegard's visions in the later mediaeval period - the mere strangeness of the image to the modern male mind seems no reason to dismiss it. K. Aland and D. Aune, specialists in early Christian prophecy, accept the text as authentic Montanist utterance.

35) Joel 2:28

36) De unitate ecclesiae 7

37) While the Latin text of the Vision surfaced in the late fourth century, historians believe that it was based on a Greek original which must have existed in the previous century.

38) quoted in Barnstone, W. (Ed.). (1984). The other bible: Jewish pseudepigrapha / Christian apocrypha / Gnostic scriptures / Kabbalah / Dead Sea scrolls. San Francisco: HarperCollins, p.542

39) quoted in Zaleski, C. (1987). Otherworld journeys: Accounts of near-death experience in medieval and modern times. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 28

40) Gallons of scholarly ink have flowed over the controversy of Constantine's imaginings. Did the vision and dream happen as reported? Did Constantine exaggerate his story, in order to stiffen the resolve of his fighters? How much did the passage of time alter what Constantine, Lactantius and Eusebius remembered about these events before they wrote their accounts? Some historians even doubt that the emperor ever seriously converted to Christianity. None of these questions can be answered with certainty. However, there is a general consensus that something profound happened to Constantine - even Paul Johnson [(1980). A history of Christianitv. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin], who is skeptical about the recorded details, grants that the Emperor "clearly underwent a strange experience" (p.68). And Constantine's role in promoting Christianity is well-established. The version presented in this chapter is a best guess.

41) Theodoretus, quoted in Le Goff, p. 219

* * * ©1999 LEONARD GEORGE * * *